Which Type of Islamic Art Was Developed Despite a Quranic Prohibition?

Introduction to Islamic Art

One surface area where the genius of the Muslim civilisation has been recognised worldwide is that of fine art. The artists of the Islamic world adjusted their creativity to evoke their inner beliefs in a series of abstruse forms, producing some astonishing works of art. Rejecting the depiction of living forms, these artists progressively established a new manner substantially diffusive from the Roman and Byzantine art of their time. In the listen of these artists, works of art are very much continued to ways of transmitting the message of Islam rather than the material form used in other cultures. This article briefly examines the pregnant and graphic symbol of art in Islamic culture and explores its main decorative forms-floral, geometrical, and calligraphic. Finally, it looks at the influence of the art adult in the world of Islam on the art of other cultures, especially that of Europe.

Rabah Saoud*

Table of contents

one. Introduction

2. Comparison with Byzantine Fine art

iii. Sources of the Islamic Art

4. The Nature and Form in Islamic Art

5. Vegetal and Floral art

half dozen. Geometrical Fine art

seven. Calligraphy

8. Influence of Islamic Art in the West

9. Conclusion

x. References

***

Note of the editor

This article was first published in July 2004. Information technology is edited here in HTML, with revision. © FSTC 2004-2010.

***

i. Introduction

The art of Islam has attracted the attending of a number of Western scholars [ane] who gained good reputations because of their contributions to the study and publicising of the field. Despite this positive attribute, their work contained an element of prejudice equally they repeatedly applied their Western norms and criteria to their evaluation of the art produced in Islamic history. In their views, far from contributing to the arts of its society, Islam has restricted, macerated and undervalued artistic inventiveness. Islam is seen every bit obstructive and limiting to creative talent and its fine art is ofttimes judged past its incapacity to produce figures and natural and dramatic scenes. Such arguments illustrate a serious misperception of Islam and its attitude to art. The view that Islam promotes harsh and simple living and rejects composure and comfort is an accusation often made by orientalist academics. This false claim is rejected by both the Qur'an and the example of Prophet Muhammad. The Qur'an, for example, permits comfortable living if it does not lead the believer astray:

"Say, who is at that place to forbid the beauty which God has brought forth for his servants, and the good things from amongst the means of sustenance" (Qur'an 7:32).

This message is emphasised over again in another poesy:

"O you who believe! Do not deprive yourselves of the practiced things of life which Allah has permitted yous, but practise not transgress, for Allah does not love those who transgress." (Qur'an 5:87).

The authentic saying of Prophet Muhammad which was narrated by Al-Boukhari:

"Allah is cute and loves dazzler."

This is perhaps the clearest translation of the position of Islam towards art. Beauty, in Islam, is a quality of the divine. The swell scholar Al-Ghazali (1058-1128) considered it to be based on ii main criteria involving the prefect proportion and the luminosity, encompassing both outer and inner parts of things, animals and humans.

The other determinant factor influencing Western scholars' views on Islamic fine art is connected to the Greek-influenced arroyo which considers the prototype of man as the source of artistic creativity. Thus, portraits and sculptures of human were seen every bit the highest work of art. According to this view, man is nature'south most magnificent and about beautiful creature and should be both the starting time and destination of man artistic endeavour. Successful works of art are those which explore the inner depth and external physical appearance of the human trunk. Maybe the highest position given to human being, in this fine art, is when divine beings are represented in his grade, or when he is represented as being created in the prototype of the Deity. Islamic art, notwithstanding, has a radically dissimilar outlook. Here, human is seen equally an musical instrument of divinity created by a supremely powerful Beingness, Allah.

ii. Comparison with Byzantine Art

Byzantine art was fundamentally based on the incorporation of Christian themes into Greek humanism and naturalism. Together, these concepts symbolised and reflected divinity. Human and nature were seen as the epitome of the divine. This new figurative art was non seeking the aesthetic per se, as in the Greek tradition, but striving to interpret concepts in Christian belief such as salvation and sacrifice.

As they do with many fields, Western scholars often relate Islamic art to Greek and Byzantine origins, claiming that the artists of the Muslim world only imitated or borrowed from these two cultures their art and reproduced it in a Muslim "dress" of Arabesque and calligraphy. Byzantine inspiration started in the early stages of the Muslim Caliphate when the Umayyad Caliphs Abd-al-Malik [2] and Al-Walid I [three] sent for Byzantine artists to decorate the Dome of the Rock (691-92) and the Great Umayyad Mosque of Damascus (705-714). Byzantine influence is seen in the iconographic themes in the Dome of the Rock, equally reflected in the mosaics of crowns and jewels of that mosque, which Grabar (1973) believed were emulating Byzantine symbols of ability. These decorations were symbols of holiness, power and sovereignty in Byzantine art. Pursuing this theme, he says:

"In other words, the ornamentation of the Dome of the Rock witnesses a witting use by the decorators of this Islamic sanctuary of representations of symbols belonging to the subdued orto the stillactive enemies of Islam" (Grabar 1973, p. 48).

Yet, Grabar later admits that the Arabs, both earlier and after Islam, used to offering their precious belongings, including crowns, to the Kaabah and hang them there [4].

In relation to vegetal representations, in Grabar'due south view, over again the artists of Islam seem to borrow from Byzantine depictions of heaven equally if they lacked any knowledge or literary clarification of it. He claims that Byzantine art was so complete and superior that the Muslims had to emulate it. Faced with the question of why the Muslims did not adopt figurative art, Grabar argued that they had to give information technology upwardly due to the superiority of the Byzantine art which they could non compete with. He says that:

"the Umayyads could hardly in one generation acquire the sophisticated practise of imagery which characterised Byzantium. Faced with this dilemma, the Muslims tried both alternatives, only soon discarded imagery, and, as we have seen adopted the techniques of Byzantium without its formulas".

Grabar clearly disregarded the opposition of Islam to imagery, which is exemplified in a number of the Prophet Muhammad sayings (see below).

Von Grunedaum (1955) provided a more comprehensive view arguing that the lack of imagery was due to the position of man in the Islamic religion. An important aspect of Muslim theology was the prominence of the attributes separating God, the Creator, and man, his favourite creature. Man is guided by and bailiwick to his fate and therefore cannot reach the position of God, which other religions say he can accomplish. The primal principles of art in Islamic culture are the declared truths that there is "no god just God" and "nothing is like unto Him"; His realm is neither space nor time and He is known by xc ix attributes, including the First and the Last, and the Seen and the Unseen, and the All-Knowing:

Allah! In that location is no god but He, the Living, the Self-subsisting' Eternal. No slumber can seize Him nor sleep. His are all things in the heavens and on globe. Who is there that can intercede in His presence except as He permits? He knows what (appears to His creatures) earlier or after or behind them. Nor shall they compass aught of His knowledge except equally He volition. His Throne doth extend over the heavens and the earth, and He feels no fatigue in guarding and preserving them for He is the Most High, the Supreme (in glory) (Qur'an2:255).

This is possibly the main partitioning in the philosophy and arroyo towards art between the Muslims and non-Muslims. With this approach, Islamic art did not need any figurative representation of these concepts. How can he depict God if he believes that He is the Unseen and aught is like unto Him? Any artistic expression of these, either in natural or human forms, would undermine the meanings and the essence of the Muslim faith. Consequently, artists engaged in expressing this truth in a sophisticated system of geometric, vegetal and calligraphic patterns (Al-Faruqi, 1973). Islam was the only religion that did not demand figurative fine art and imagery to establish its concepts (Von Grunedaum, 1955).

three. Sources of Islamic Art

Like other aspects of Islamic civilization, Islamic art was a outcome of the accumulated knowledge of local environments [5] and societies, incorporating Arabic, Western farsi, Mesopotamian and African traditions, in addition to Byzantine inspirations. Islam built on this cognition and developed its ain unique style, inspired by three primary elements.

The Qur'an is seen as the offset piece of work of fine art in Islam and its chef-d'oeuvre (Al-Faruqi, 1973). The independence of some verses and the interrelation of others form boggling meanings equally each verse takes the reader into a unique divine experience feeling its joy and happiness, terror and fearfulness, bliss and anger, and and so on. The abiding repetition of these experiences in the verses of the Qur'an "winds up consciousness and generates in it a momentum which launches information technology on a continuation or repetition and infinitum" (Al-Faruqi 1973, p.95). The terminal outcome of this experience makes the reader experience the presence of God as described in the poesy:

"when the verses of the Beneficent are recited unto them, they fall down prostrate in adoration and tears" (Qur'an 19:58).

As a result, artists drew lessons and methods from their feel of the Qur'an, developing a new approach to art characterised by the independence and interdependence of its formative elements. The emphasis was on the presence and attributes of the divine Creator rather than on His creatures, including man. Islam sees all men equal regardless of colour or course (perfect or imperfect). The merely distinction between them is fabricated on the basis of their piety. Consequently, Islam sees the white-skinned and fair-haired platonic of man promoted by Western art as racial and misleading.

The second element comes from the Qur'anic verses which criticises poets every bit:

"As for the poets, the erring follow them. Accept you not seen how they wander distracted in every valley? And how they say what they practice not? (Qur'an 26:224-26).

This formula regulates the approach of artists, writers and professionals. Islam only approves work from

"those who believe, do good work, and appoint much in the remembrance of Allah" (Qur'an 26:227).

With this background, the artist'south work was guided past this criterion and was e'er connected to the remembrance of God whether it was in ceramics, cloth, leather or atomic number 26 work or wall decoration. The means this remembrance was expressed was, of form, many. Artists worked with many dissimilar materials, from ceramic to iron, and their artistic mode took many forms, such every bit Arabesque designs, geometrical patterns and calligraphy.

The third decisive factor dictating the nature of art in Islamic culture is the religious rule that discourages the depiction of homo or fauna forms [half-dozen]. The presence of this rule is due to a concern that people would get dorsum to the worship of idols and figures, a exercise that is strongly condemned past Islam. In the early on days of Islam, sculpture and imagery were seen as reminders of the despised idolatrous by. Today, the bulk of Muslims withal respect this rule and their attitude extends to dislike the excessive "trunk worship" practised in the West. The latter can exist seen in the revival of Islamic clothes among educated Muslim women and in their avoidance of the excessive use of make-up.

Furthermore, Islam is costless from metaphysical arguments such as those relating to the trinity, the true nature of Christ, the Holy Spirit and saints bureaucracy, as constitute in Christianity. Consequently, at that place was no need in the mosque for apses, transepts, crypts likewise as images and sculptures of saints, angels and martyrs that played a prominent part in didactic art in Christian churches. Notwithstanding, in that location were some instances where human and animal forms were used in Islamic fine art, but these were mainly found in secular private buildings of some princes and wealthy patrons. Discoveries made in the Qasre Amra palace, congenital by the Umayyad Caliph Al-Walid I (705-715) in the Jordanian desert, revealed big illustrations of hunting scenes, gymnastic exercises, and symbolic figures. The most important of these were illustrations depicting the principal enemies of Islam, Kaisar (the Byzantine Emperor), Roderick (the Visigoth Rex of Spain), and Khosrow (the Emperor of Persia). There was also an illustration of the Negus, the Abyssinian king, who gave the Muslims refuge when they were beingness prosecuted in Mecca in the early on days of Islam [7] (Creswell 1958, p.92).

In relation to the depiction of creature forms, many examples were discovered. Lions and eagles, for example, were institute in illustrations of hunting scenes, and carved in sculptures and heraldic emblems. These emblems were transmitted past the Crusaders to Europe where they were widely copied.

four. The Nature and Form in Islamic Art

Islamic art differs from that of other cultures in its class and the materials it uses as well as in its field of study and significant. Philipps (1915), for case, thought that Eastern fine art, in full general, is mainly concerned with colour, unlike that of western fine art, which is more interested in form. He described Eastern art equally feminine, emotional, and a matter of color, in contrast to Western fine art which he saw as masculine, intellectual, and based on plastic forms which disregarded colour. Of grade this reflected Philipps' cultural and creative bias. Art in Islam never lacked intellectualism even in its simplest forms.

The invitation to observe and acquire is establish in both revealed and hidden messages in all its forms. Bourgoin (1879), on the other manus, compared the art forms of Greek, Japanese and Islamic cultures and classified them into three categories involving fauna, vegetal, and mineral respectively. In his view, Greek fine art emphasised proportion and plastic forms, and the characteristics of human and fauna bodies. Japanese fine art, on the other manus, developed vegetal attributes relating to the principle of growth and the dazzler of leaves and branches. However, Islamic fine art is characterised by an illustration between geometrical design and crystal forms of sure minerals. The main divergence between information technology and the art of other cultures is that it concentrates on pure abstract forms as opposed to the representation of natural objects. These forms take various shapes and patterns. Prisse (1878) classified them into three types, floral, geometrical and calligraphic. Another classification was suggested by Bourgoin (1873) involving ornamental stalactites, geometrical arabesque, and other forms. For our decorative interest, we concentrate on the three forms suggested by Prisse, which announced, either alone or together, in most media, such every bit ceramics, pottery, stucco or fabric.

|

| Figure 1: Detail of a floral decoration in the Dome of the Rock Mosque. |

5. Vegetal and Floral art

Although, Muslim art was non, of course, developed independently of influences from nature and the surroundings, their representation was abstract rather than realistic, as in Western art. This is seen clearly in vegetal forms where plant branches, leaves, and flowers were woven and interlaced into and oftentimes not distinguished, from the geometrical lines around them as seen in the arabesque. The use of vegetal forms in Islamic fine art is also conditioned to some extent by the Islamic prohibition of the faux of living creatures. Even so, this interdiction naturally decreases with the descent from human to beast to vegetable forms. Art critics describe the floral depictions and ornaments of the artists of Islam as conventional; lacking the furnishings of growth and the cosmos of life (Dobree 1920). In their stance, the reason backside the absence of growth was due to the natural surroundings of the Muslim countries, where the experience of bound, the season of plant growth is fleeting. Withal, the religious prohibition mentioned above was behind the absence of lifelike creation in much of the Islamic floral fine art.

|

| Figure 2: Illustration of a tree in a landscape decoration in the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus. |

In the Dome of the Stone and the Umayyad Mosque of Damascus, which contain the primeval examples of Islamic vegetal fine art, we find more realistic depictions of plants and trees, but these examples, every bit noted before, are regarded every bit Byzantine work for the Umayyad patrons. In dissimilarity, the vegetal decoration in Samarra Mosque (Iraq) shows how artists, in dissimilarity, deliberately reproduced the vine leaves and branches in an abstract form. Withal, by the 13thursday century a more realistic approach gradually gained ground in Muslim Persia and Turkey, influenced by the Chinese and the Mongols (Al-Ulfi, 1969, p.114).

The Muslims used foliage with great delicacy especially effectually the arches and windows. The stucco borders used in the mausoleum of the Ayyubid Sultan Qalawun, built in Cairo (Egypt) in 1284/85, consisted of buds and leaves arranged in a continuous scroll pattern. The mausoleum also contained examples of other floral illustrations set in rectangular and circular panels, a feature which became particularly popular in the 15th century (Poole, 1886). The use of this type of fine art extended to many ornamental objects, such as pottery, and wood and leather carving as well as coloured tiles.

half-dozen. Geometrical Fine art

The 2d chemical element of Islamic art involves geometrical patterns. The artists used and developed geometrical art for two master reasons. The start reason is that it provided an alternative to the prohibited depiction of living creatures. Abstract geometrical forms were particularly favoured in mosques considering they encourage spiritual contemplation, in contrast to portrayals of living creatures, which divert attending to the desires of creatures rather than the will of God. Thus geometry became central to the art of the Muslim World, assuasive artists to complimentary their imagination and creativity. A new class of fine art, based wholly on mathematical shapes and forms, such as circles, squares and triangles, emerged.

The second reason for the development of geometrical art was the sophistication and popularity of the science of geometry in the Muslim world. The recently discovered Topkapi Scrolls [eight], dating from the 15th century, illustrate the systematic use of geometry by Muslim artists and architects (see Gülru, 1995). They also evidence that early Muslim craftsmen developed theoretical rules for the utilise of aesthetic geometry, denying the claims of some Orientalists that Islamic geometrical art was developed past blow (e.g. H. Saladin 1899).

This geometrical art is very much connected to the famous concept of the arabesque, which is defined as "ornamental piece of work used for flat surfaces consisting of interlacing geometrical patterns of polygons, circles, and interlocked lines and curves" (Chambers Science and Engineering Dictionary 1991).

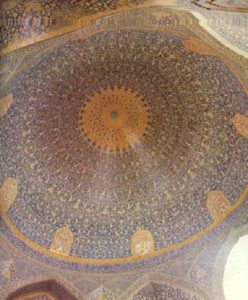

|

| Figure 3: Floral Arabesque covering the interior of the dome of Masjid-i Shah Mosque, Isfahan (16111616). |

The arabesque pattern is equanimous of many units joined and interlaced together, flowing from each other in all directions. Each unit, although information technology is independent and consummate and tin stand lone, forms part of the whole design; a annotation in the full general rhythm of the design (Al-Faruqi 1973). The near common use of arabesque is decorative, consisting mainly of a two dimensional pattern, roofing surfaces such as ceilings, walls, carpets, article of furniture, and textiles. From his report of 200 examples, Bourgoin (1879) ended that this style of art required a considerable cognition of practical geometry, which its practitioners must take had. In his view, the arabesque pattern is built upwardly on a arrangement of articulation and orbiculation and is ultimately capable of existence reduced to i of nine elementary polygonal elements. The pattern may exist built upward of rectilinear lines, curvilinear lines, or both combined together, producing a cusped or foliated outcome. Information technology is reported that Leonardo da Vinci plant Arabesque fascinating and used to spend considerable fourth dimension working out complicated patterns (Briggs, 1924, p.178).

Arabesque tin too exist floral, using a stem, leaf, or flower (tawriq) as its artistic medium, or a combination of both floral and geometric patterns. The expression embodied in its interlacing pattern, cohesive movement, gravity, mass, and volume signifies infinity and produces a contemplative feeling in the spectator leading him slowly into the depth of the Divine presence (Al-Alfi 1969). Dobree (1920) explained the impact of Arabesque art as follows:

"Arabesque strives, not to concentrate the attending upon any definite object, to liven and quicken the appreciative faculties, simply to diffuse them. Information technology is centrifugal, and leads to a kind of brainchild, a kind of cocky-hypnotism fifty-fifty, so that the devotee kneeling towards Makkah can bemuse himself in the maze of regular patterning that face up shim, and free his mind from all connectedness with actual and earthly things" (quoted in Briggs1924, p.175).

It is clearly axiomatic that much of the credit for the development and the popularity of geometrical art goes to the artists of the Islamic world, although its origins are still debated. Claims have been made that primitive geometrical ornament was used in Ancient Egypt besides as in Mesopotamia, Persia, Syria, and Republic of india. The star pattern, for example, was widely used by the Copts of Egypt (Gayet, 1893), but the artists of the world of Islam were its all fourth dimension masters.

|

| Figure 4: Kufic Lettering (from Al-Jiburi, 1974). |

seven. Calligraphy

The tertiary decorative form of art developed in Islamic civilization was calligraphy, which consists of the use of creative lettering, sometimes combined with geometrical and natural forms. As in other forms of Islamic art, Western scholars attempted to chronicle calligraphy to the lettering art of other cultures. The decorative utilize of letters in both China and Nippon seem to exist an area of interest to them. Theories challenge that the development of Islamic calligraphy was influenced by the Chinese, dubiously based on the pottery found in old Cairo (Al-Fustat), seem to be absurd (Christie, 1922). The lack of whatever substantiated proof is clear evidence as are the wide differences betwixt the two languages in the way and the management they are written. The proffer of whatsoever link between Islamic calligraphy and ancient is also inconceivable. Information technology is true that the aboriginal Egyptians widely used hieroglyphics on wall paintings, but these had no decorative purpose (Briggs 1924, p.179).

|

| Figure 5: Kufic calligraphy combined with floral and geometrical ornamentation with intersecting horseshoe arches. Plate on Cordoba Mosque façade. |

The development of calligraphy as a decorative fine art was due to a number of factors. The get-go of these is the importance which Muslims attach to their Holy Book, the Qur'an, which promises divine blessings to those who read and write information technology downward. The pen, a symbol of knowledge, is given a special significance by the verse:

"Read! Your Lord is the Virtually Bounteous, Who has taught the utilise of the pen, taught homo what he did not know" (Qur'an 96:3-v).

This indicates that the aim of Islamic calligraphy was not merely to provide decoration merely too to worship and remember Allah. The Qur'anic verses mostly used are those which are said in the human activity of worship [9], or contain supplications, or depict some of the characters of Allah, or his Prophet Muhammad. Calligraphy is likewise used on dedication stones to record the foundation of some central Islamic buildings. In this case, a man is referred to every bit the founder, oftentimes a Caliph or an Emir, but he was consciously described as poor to Godor Slave of God, a reminder of his position before Allah.

The second factor backside the advent of Arabic calligraphy is attached to the importance of the Arabic language in Islam. The use of Arabic is compulsory in prayers and it is the language of the Qur'an and the language of Paradise (come across Rice, 1979). Furthermore, the Arabs have ever attached a considerable importance to writing, emanating from their appreciation of literature and verse. It is reported that the Prophet Muhammad said:

"Seek prissy writing for it is one of the keys of subsistence" and the fourth Caliph, Ali commented on calligraphy as:

"The beautiful writing strengthens the clarity of righteousness"

(both quotes from Al-Jaburi 1974).

In improver, the mystic power attributed to some words, names and sentences equally protections against evil also contributed to the development of calligraphy and its popularisation.

Arabic calligraphy was mostly written in 2 scripts [10]. The commencement is the Kufic script, whose proper name is derived from the urban center of Kufa, where information technology was invented past scribes engaged in the transcription of the Qur'an who set up a famous school of writing [11]. The letters of this script have a rectangular class, which fabricated them well suited to architectural use.

|

| Figure half dozen: Transcript of Naskhi calligraphy past Mahmud Yazre. |

The other script of Arabic calligraphy is known as Naskhi. This style of Arabic writing is older than Kufic, even so information technology resembles the characters used by modernistic Arabic writing and printing. It is characterised by a round and cursive shape to its letters. The Naskhi calligraphy became more popular than Kufic and was substantially developed by the Ottomans (Al-Jaburi 1974).

viii. Influence of Islamic Fine art in the W

In full general, the diffusion of the Islamic art motifs to Europe and the rest of the world occurred in three different ways. The first of these was direct imitation through the reproduction of the same theme in the same blazon of medium. For case, an creative theme (or themes) in an Islamic ceramic could have been reproduced in a European ceramic. There are a multitude of examples of this kind of imitation. Possibly the most widely acknowledged ones are the many instances of copying of Kufic inscriptions in Medieval and Renaissance European art. According to Christie (1922), Kufic inscriptions in the Ibn Tulun Mosque, built in Cairo in 879, were reproduced in Gothic art first in France, so in the rest of Europe. Lethaby (1904) also attributed to the carved pattern of wooden doors in a chapel of the Cathedral of Le Puy (France), and of another door in the church building of la Vaute Chillac nearby, which were made by the Chief carver "Gan Fredus". This connection is attributed to the special human relationship Amalfi had with Fatimid Cairo at that time. Amalfitan traders visiting Cairo were believed to be responsible for the transmission of these motifs to Europe.

|

| Figure 7: Tiles in the Alhambra Palace showing geometrical Decorations and Naskhi Calligraphy, Granada, Spain. |

Male (1928) constitute traces of Islamic influence in many religious buildings of Southern French republic, in the region known every bit the Midi. The listing of Islamic motifs, which he collated from these buildings, included horseshoe and multifoil arches and polychromy. Male person believed they were copied from Andalusia. Islamic influences were also traced in Westminster Abbey in London, in bands of ornaments in the retable also equally in the earlier stained glass windows (Lethaby 1904). This was non all. Motifs such as the 8 pointed star, the stalactite, the Ottoman blossom (tulip and carnation) and Alhambra geometrical and colour schemes are just a few items that form an essential part of most European works of art (see Fikri 1934) [12]. In improver, it is widely held that Gothic geometrical medallions such as polyfoil, quatrefoil or the foliated foursquare were also of Islamic origin (Marcais, 1945).

The 2nd way Islamic art motifs were transferred to Europe was through the transposition of source or media. In this example, an Islamic theme in a particular medium was reproduced in a European piece of work of art in a different blazon of medium. For example, a theme in an Islamic ceramic work could have been reproduced in European furniture, textile, sculpture and so on. Examples of this type of transfer are once again very all-encompassing, and we cannot cover them all hither. The example of arabesque must suffice. According to Ward (1967), the fertilisation of European ornamental art during the Renaissance (16thursday century) was at the hands of arabesque. Arabesque and other Islamic geometrical patterns invaded European salons, living rooms, and public reception halls.

|

| Figure 8: View of Al-Azhar mosque courtyard in Cairo. |

The third fashion of transfer is the most difficult to explain. Here, the motif was non copied or reproduced simply gradually inspired the development of a detail style or fashion of art. There is increasing evidence that Islamic art, and the arabesque in particular, was the inspiration for both the European Rococo and Bizarre styles which were popular in Europe between the 16th and 18thursday centuries (Jairazbhoy, 1965). The Rococo manner consisted of light curvilinear decoration composed of abstract sinuosities such equally scrolls, interlacing lines and arabesque designs. It was developed in French republic in the 18th century, and later spread to Germany and Austria. The germ of this manner is found in the Islamic Aljaferia Palace (as well known as Hudid Palace), built in northern Spain in the eleventh century, where a number of blind arches and squinches in a manner very similar to Rococo decorate its small mosque (Jairazbhoy, 1973). Other examples of this early "Islamic Rococo" are found in the Great Mosque of Tlemcen, People's democratic republic of algeria, which was built in 1136.

Baroque architecture has too been traced back to an Islamic origin. According to some sources (for example Jairazbhoy 1965), the word "bizarre" is ultimately derived from the Arabic word of burga, meaning "uneven surface", which was the source of the word barrocco in Portuguese, which meant "irregularly shaped pearl".

|

| Figure ix: Decorative arcade in Aljaferia showing elements that later inspired the Baroque style. |

Muslims used motifs such as curviangular arches and squinches, which characterise the Baroque style, in their decorative art as early as the 12th century. They became especially pop under the Almoravid rulers (al-Murabitunin Standard arabic) who ruled North Africa and Andalusia between 1062 and 1150.

|

| Figure x: Northern archway of the Ulu Cami Hospital (13th century) showing a close upwards view of "Baroque" features. |

In add-on to the above, a more than complicated decorative style, consisting of a combination of multifoil arches intersecting with one another like a screen mesh, is plant in the Aljaferia Palace equally well as in mosques of Tlemcen (1136) and Qarawiyyin, built in Kingdom of morocco between 1135 and 1143. Another case is the Ulu Cami Infirmary in Divrighi, Turkey, completed in 1229, which shows a remarkable resemblance to Baroque in its ornamentation and décor, even though it predates it by 4 hundred years.

9. Conclusion

The main objective of this paper has been to emphasise the uniqueness of Islamic art, which was defined by religious behavior and cultural values prohibiting the depiction of living creatures including humans. The other most important characteristic is the absence of religious representation. In Islam, worship is due simply to God, a characteristic common to many cultures, although they approach it in different manners. Fine art critics propound the neutrality of Islamic art, which made information technology easily adaptable to these cultures. Due peradventure due to its geographic proximity and religious "common ground", no other civilization was more exposed to the themes and motifs of Islamic art than the European. Despite their differences, Islam and Christianity share almost of their primal behavior which are continued to the same God, the same origin (of the message), and sometimes the same moral message. It is not surprising that vestiges of Islamic art were repeatedly traced in major European artworks, a fact which denotes its significance in the historical development of European art.

x. References

- Al-Alfi Abu Saleh (1969). The Muslim Art, its origins, philosophy and schools (in Arabic). Dar Al-ma'arif, Cairo.

- Al-Faruqi, R. (1973). "Islam and Art", Studia Islamica, vol. three seven, Larose, Paris, pp. 81-110.

- Al-Jaburi, Mahmud Shukri (1974). The Birth of Arabic Calligraphy and its development (in Standard arabic). Library Al-shark al-Jadid, Baghdad.

- Bourgoin, J. (1873), "Les Arts Arabes", Paris. (Cited by Briggs 1924).

- Bourgoin, J. (1879). Les Eléments de I'Art Arabe, Paris. (Cited by Briggs 1924).

- Briggs, M.S. (1924). Muhammadan Architecture in Egypt and Palestine. Clarendon Printing, Oxford.

- Christie, A. H. (1922). "Development of ornament from Arabic manuscripts", Burlington Mag, vo. 41, pp.286-288.

- Creswell K.A.C. (1958). A Short Account of Early Muslim Architecture. Penguin Books, London.

- Dieulafoy, M. (1903). Art in Spain and Portugal. Heinemann, London.

- Dobree, B. (1920). "Arabic Art in Arab republic of egypt", The Burlington Magazine, vol.36, pp.31-35.

- Fikri, A. (1934). L'Art de Roman du Puy et les influences islamiques, Librairie Ernest Leroux, Paris.

- Gayet, A. (1893). L'Fine art Arabe', Paris.

- Grabar, 0. (1976). "The Umayyad Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem", in Grabar, 0. (1976), Studies in Medieval Islamic Art, Variorum Reprints, London, pp. 33-62.

- Grabar, 0. (1976). "Islamic Fine art and Byzantium", in Grabar, 0. (I 976), Studies in Medieval Islamic Art, Variorum Reprints, London, pp. 69-83.

- Jairazbhoy, R. A. (1965). Oriental Influences on Western Art. Asia Publishing House, London.

- Lethaby, W.R. (1904). Medieval and Co. London, Charles Scribner's Sons, New York, vol.4.

- Male, E (1928). Art et Artistes du Moyen Age. Libraxie Armand Colin, Paris.

- Marcais, K. (1945). "Le intendance quadrilobe: histoire d'une forme décorative de l'fine art gothiqueé, Etudes d'art du Musée d'Alger, vol. ane, pp. 67-78.

- Gulru, Necipoglu, et.al. (1995). The Topkapi Curl: Geometry and Decoration in Islamic Architecture. Geny Research Constitute.

- Poole, L. (1886). Saracenic Art. London.

- Prisse d'Avennes (1878). L'Art Arabe d'après les monuments du Caire. Morel, Paris.

- Read, R. (1937). Art and Society. Heinemann, London.

- Read, H. (I 949). The Meaning of Art. Penguin Books, London.

- Saladin, H. (1899). La Grande Mosquée de Kairawan. Paris.

- Rice, D.T. (1979). Islamic Fine art. Tharnes & Hudson, Norwich.

- Von Grünebaum, G. E. (1955). "Idéologie musulmane et esthétique arabe", Studia Islamica, vol. 3, Larose, Paris, pp. 5-23.

- Walker, P. Yard. B. (editor), (1990), Chambers Science and Applied science Lexicon. Chambers Harrap Publishers, Hardcover.

Footnotes

[1] Notably R. Ettinghaussen, East. Herzfeld, K. A. C. Creswell, and A. Grabar.

[ii] Reigned betwixt (685-705).

[3] Reigned between (705-715).

[4] Until the fourth dimension of Ibn Zubayr, who ruled Makkah betwixt 678-693, The Kaabah was adorned with the horns of the ram sacrificed by the Prophet Ibrahim, in place of his son Ismail. The Caliph Umar Ibn Al-Kahttab as well hung in that location ii crescent shaped ornaments from the Western farsi Capital, Al-Madain. About of the successive Umayyad and Abbasid Caliphs also sent precious items to the Kaabah as gifts, to decorate the House of Allah.

[5] Read (1937), for example, talked about environmental determinism in art. He argued that there are two chief approaches to artistic expression: organic and geometric. The quondam appears mainly in areas of natural beauty and favourable surround. In this case, the artist is more attracted to depicting beautiful landscapes, seashores, plants, animals and humans. Geometric fine art, on the other manus, appears in societies of harsh natural and ecology conditions such every bit deserts or tundra.

[half-dozen] Although no reference to their prohibition is establish in the Qur'an, a number of authentic sayings of the Prophet Muhammad did preclude them. An example of this is the Hadith reported by Muslim who narrated that Ibn Abbas: "I heard the Messenger of Allah saying: 'All those who paint pictures will be in the Fire of Hell. The soul will be breathed in every picture prepared by the man and it punishes them in Hell" (Narrated by Muslim, 3945). Muslim scholars take different views on this thing. Some of them, particularly those from the Shia school of thought allow the imaging of living beings. Others, such as Mohammed Abdu, let imagery and photography as long they exercise not conflict with i's beliefs or worship. Al-Ulfi (1969) reported that he said of photography: "In general I am inclined to call up that Islamic law (Shariah) does non forbid ane of the best means of learning, especially if it does non conflict with the Islamic beliefs and worship" (run into Al-Ulfi, 1969, p.84).

[7] Information technology is believed that he converted to Islam. It was reported that on hearing about his death, the Prophet Muhammad performed prayers for his soul.

[eight] The scrolls, thought to be a Timurid manuscript, comprise 114 individual geometric patterns for wall surfaces and vaulting.

[9] Surah Al-Fatiha, for example, is specially favoured since it is the opening of the Qur'an and is said in all prayers.

[x] From these two chief styles, a number of other sub-styles emerged as calligraphers introduced new modifications to the original fashion. The most familiar ones are Thuluth, Al-Rakaa, Al-Diwany, Jali Diwany, and Persain.

[xi] According to Al-Jaburi (1974), later the establishment of Kufa, some Yemeni tribes who knew an early course of this lettering style settled there. This style attained its complete shape under the reign of the quaternary Caliph (Ali), between 657 and 661, who was a calligrapher himself.

[12] This excellent PhD thesis published by A.Fikri was devoted to the influence of Islamic art and architecture on southern French republic, particularly in the Auvergne region.

*Dr Rabah Saud wrote this article for www.MuslimHeritage.com when he was a researcher at FSTC in Manchester. He is now Assistant Professor at the Academy of Ajman, Ajman, UAE.

Source: https://muslimheritage.com/introduction-to-islamic-art/

0 Response to "Which Type of Islamic Art Was Developed Despite a Quranic Prohibition?"

Post a Comment